Artist Margaret Meehan of Dallas, Texas bases her work on extensive historical research, gathering images and information that become the foundation of her work. Meehan mines and utilizes historical and cultural subjects, layering information to reveal new discoveries and establish new truths. Despite her diverse sources, themes of otherness, duality, and memory have been consistent in her work for the past two decades.

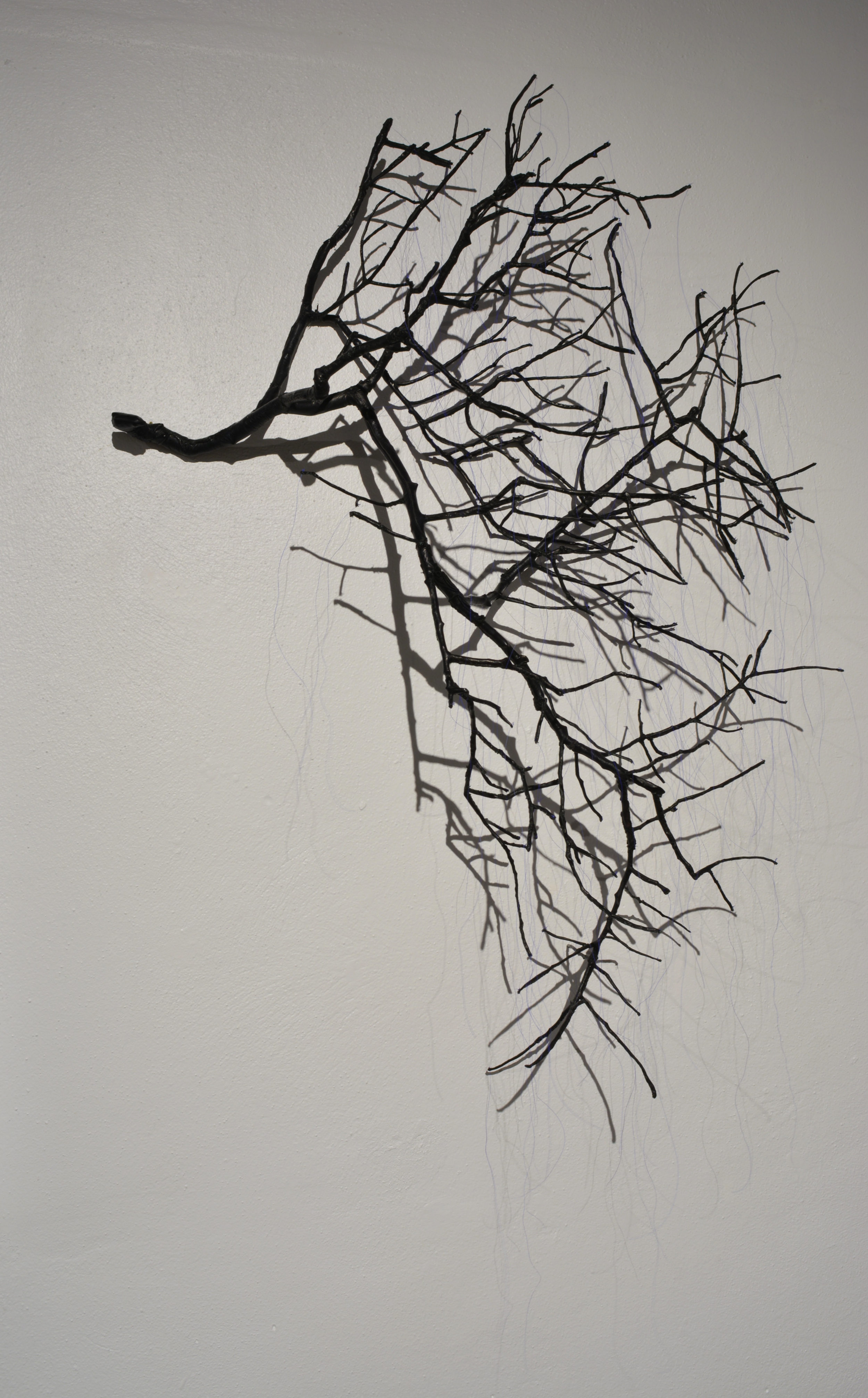

Meehan’s adeptness with materials knows no limits as she incorporates painting, sculpture, photography, collage, drawings, sound, and video into thoughtful and visually complex installations. Collaborations with writers are sometimes utilized in her exhibits adding yet another layer that parallels and compliments the visual information.

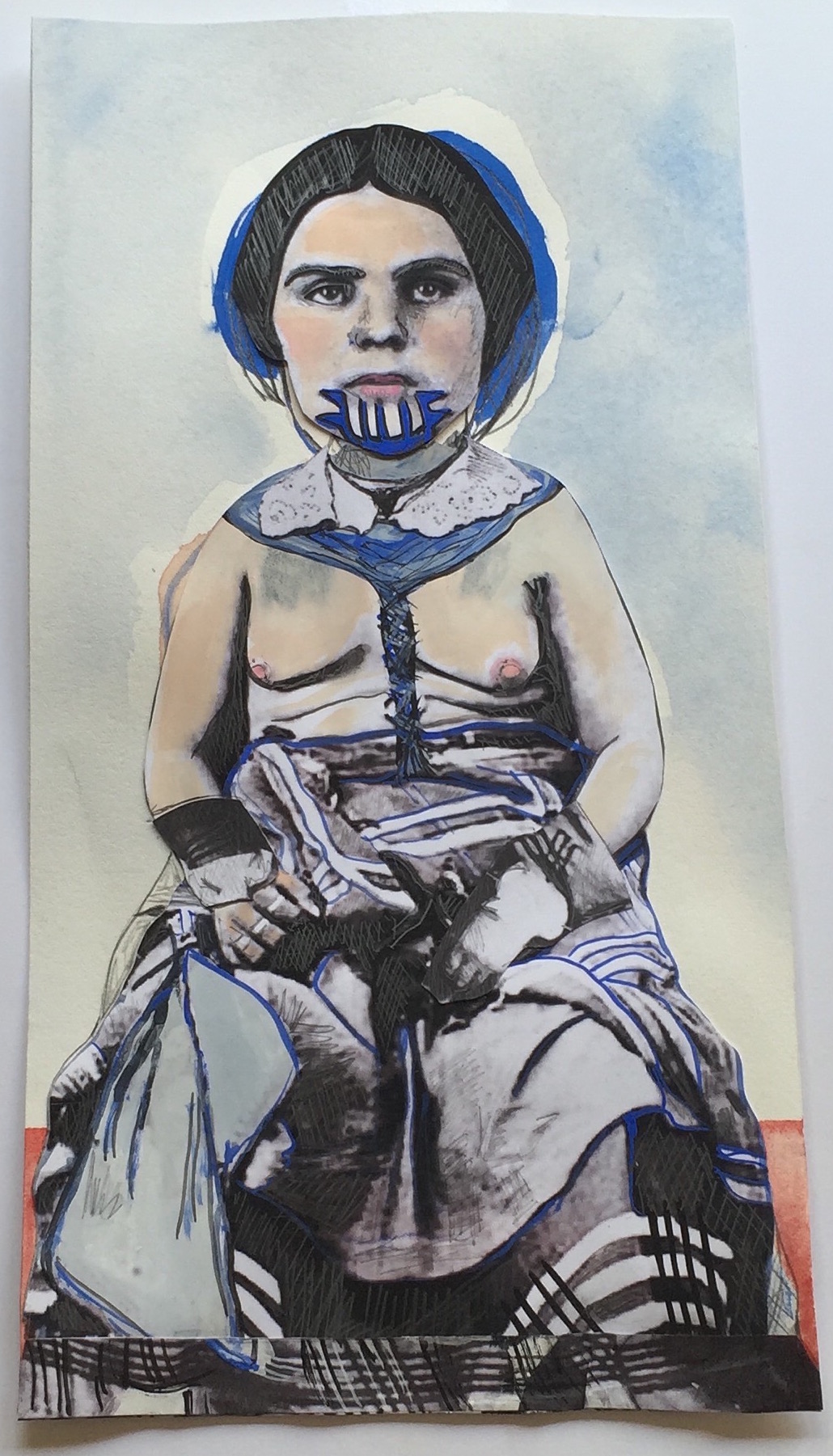

Meehan’s exhibition at the OJAC, Bye Bye Blue, is based on multiple versions of an erased and reinvented past of the historical figure, Olive Oatman, as well as her infamous blue tattoo. In 1851, Oatman was captured, traded, and enslaved for five years by Native American tribes before returning to white society. Thoughtfully weaving this theme with others, she offers an installation that challenges the viewer to interpret the work through numerous access points of individual interest.

Patrick Kelly, the Old Jail Art Center’s Curator of Exhibitions, email interview with Margaret Meehan. (April/May 2016)

PK: I want to start out by asking about your mode of approaching a particular series of works. It appears that you do extensive historical research into a subject of interest. Can you talk about how that transpires?

MM: Yes, research has become a larger component of my process; to the extent that I now consider it part of the work. I’ve dealt with variations of the same subject matter over the past 20 years: otherness, duality and memory. My research consists of gathering images and information constantly. I file images and ideas away in my sketchbook, on my computer and on my blog http://upliketoast.blogspot.com. I look at academic history and popular culture equally and let each inform the other. Visual art, music, novels, cinema, journalism, and medicine layer to reveal a direction for a body of work. It’s like a spider web and it’s always amazing when an idea starts to take shape.

I’m interested in the ways that bodies, either through medical anomalies, race, gender or sexuality, can challenge the myth of a homogeneous society. I hope that by unraveling and revealing forgotten histories I can reflect the complex ways in which we deal with difference and suggest a more hopeful future if we look at and learn from the past.

PK: In your research, are you sometimes skeptical about the accuracy or truthfulness of history? Does this concept interest you and become a part of the work?

MM: I am always skeptical about the accuracy of history. To me it’s a lot like memory. The story changes depending on who is telling it and how many times it has been retold. I’m not so much interested in finding the truth as I am in trying to see its origins and discovering or reinventing a new truth. I think I’m really just trying to continue to learn more myself and make sure I’m always questioning.

PK: In 2014, you were an artist-in-residence at Artpace in San Antonio. Decoration Day was your exhibition as a result of your residency. One theme was women’s service in the military, with a primary focus on those that fought in the U.S. Civil War. Was there one text or image that sparked that eventual body of work? And if so, can you describe how that one item “spider webbed” into an entire exhibition?

MM: Yes, Decoration Day began with an interview I heard on NPR about the book They Fought Like Demons: Women Soldiers in the Civil War by De Anne Blanton and Lauren M. Cook. I was spending a lot of time in the studio getting ready for a solo show in Houston and listening to stories on the radio about Wendy Davis’s 11 hour filibuster against a bill that included stiff restrictions on abortion across the state, and how her actions were putting Texas on the national map. About this time, I had a studio visit with N’Goné Fall an independent curator based in Paris and Senegal who had been sent by Artpace to choose the Summer 2014 residents. She saw 3 books I had out: They Fought Like Demons, The Blue Tattoo: The Life of Olive Oatman (Women in the West) by Margot Mifflin, and Southern Horrors: Women and the Politics of Rape and Lynching by Crystal M. Feimster. Southern Horrors was the basis for what I was working on in the studio at that moment. But when I showed her the book on women of the Civil War she told me a great story about her grandmother and we bonded on how women have been fighting equally with, for, and as men to defend what they believe in for centuries. We talked about how the attributes assigned to genders are limiting and misleading and how terms like “honor,” “strength,” and “bravery” are not just masculine descriptives. She asked me about Wendy Davis and we talked about women in Texas, America and around the world. Then she asked me if I was a feminist, which led to a whole other conversation. It was so great and inspiring. It was one of the best studio visits I’ve ever had because not only did we talk about the actual work, but also the ideas behind it. It was a real conversation. A few months later I found out I was lucky enough to be chosen by her and this is when those female soldiers popped back into my head. I could have focused the residency on anything and even considered the story of Olive Oatman, who now two years later is the topic of this exhibition at the Old Jail. But, because of my conversation with N’Goné, the fact that San Antonio is a big military town and a recent story I heard about a female soldier who lost her wife—also a US soldier—in combat but was refused spousal rights, I decided on this subject.

So I researched Decoration Day by reading books and articles, listening to podcasts and watching documentaries, not only about the forgotten soldiers of the past but also about the stories of contemporary female American soldiers who have died in combat since 2001. I began looking at the policy of “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” and connecting it to the way the female Confederate and Union soldiers both hid their identity on the battlefield. Who knew, who cared, and who just needed a warm body on the front lines? I learned that their fighting was not really a secret during or after the Civil War. Many families told stories of sisters and aunts who fought as men, or wives who disguised themselves to fight alongside their husbands. It has been a forgotten history that now seems to be coming to light, like many of our country’s “unknown” pasts. My digging was about finding ways to connect these women (and later all LGBTQ individuals) to the present.

This research also led to material choices such as my use of tintypes and a ballistic jacket, as well as specific imagery that I would use for the exhibition. Timothy O’Sullivan’s historic photo A Harvest of Death, was repeated on fabric and wallpaper because it depicted not only the horrors of war but also the great number of unknown dead. It became the perfect symbol for me as it captured one of the main reasons why we don’t know the exact number of women who fought. It is estimated between 400 and 1000 women enlisted as men, but since many were buried en mass, they were buried anonymously. I could talk about this for hours but it’s probably easier for people to look at my research blog Up Like Toast. It shows all of my interests since 2008 and how I organize. If you want to see or read more about what went into Decoration Day you can click the category “The Lost Cause.” I have other categories such as gender, music, hair, horror, patterns, and birds. Some of these are minor tangents and some lead to bigger ideas, which overlap each other and sometimes become another body of work.

For example while I was at Artpace, some of my research started to focus on horror films after WWI and WWII, and how the mutated bodies of returning soldiers were being reflected in American and German cinema. (Another great book is The Monster Show by David J. Skal). This led me to my next exhibition in the fall of 2014 at Conduit Gallery titled Paper Moon. That show then led to Every Witch Way but Loose at David Shelton Gallery, which had to do with monsters, expectations of beauty, constructs of gender and race, age and physical anomalies, culpability and again, lost histories. All of these projects have so many overlapping interests, and now they are all present to varying degrees in Bye Bye Blue for the Old Jail Art Center. The constant is difference and the possibility of empathy for otherness.

PK: That’s a thorough and concluding answer, but I will ask one last question. Do you feel that the physical art objects are sometimes inadequate to fully express specific ideas spawned by the research? Or, is the work an independent manifestation and result of all your research and interest?

MM: Well to be clear—I don’t consider myself a historian or sociologist. I’m a maker who gets the most satisfaction from using my hands to create. My research is part of my practice and definitely the work would not be made without it, but it is never the final form for me. Sometimes I collaborate with writers. For instance, I worked with Andy Campbell on an online project space that I did for the publication Might Be Good in 2012, in conjunction with the exhibition Hystrionics and the Forgotten Arm at Women and Their Work. I sent Andy images and links related to my process and he wrote an amazing essay that informed and elaborated. I did a version of this with Noah Simblist as well, but our collaboration became an object that was displayed and existed as part of the exhibition We Were Them in 2013. Noah wrote mostly about my research material, not me or the artwork. The end result was a broadside that viewers could take, with one of my photographs from the show on the front and Noah’s essay on the back alongside source images. Travis LaMothe designed it and it really was a collaboration between the three of us. These are two examples that illustrate the importance of mining history for me, but also that this process is meant to inform my studio practice, not replace it. I hope that my objects give people a sense of my interests and they become as curious as I am, maybe getting them to read or do their own investigating. But in the end, the objects and installations should speak for themselves, and my hope is that there are multiple access points for my audience to enter.