Mourning Dress, 2014

Custom printed linen, millinery ribbon and notions, velvet forget-me-nots, crinoline, steal, paint.

60H” x 42L” x 42D”

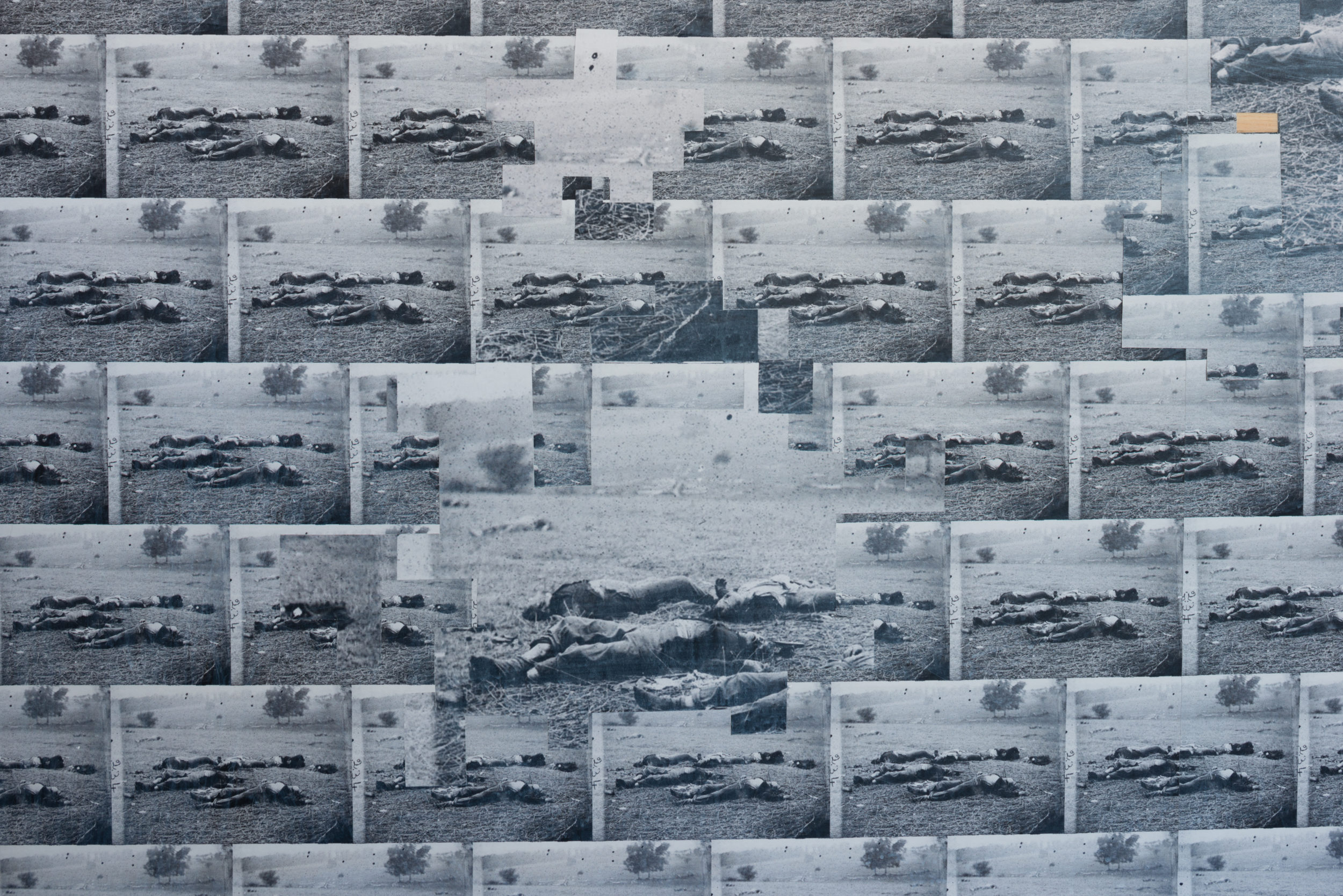

Obstacle, 2014,

Wood, wallpaper, collage, paint, 71H” x 96L “x 38W”

Soldier Boy, 2014.

Wood, horn speaker, amplifier, cord,

18:03 min single channel audio file

120H” x 47L” x 47W”

Decoration Day– Installation overview. 2014. Dimensions variable.

Unknown Soldier, 2014

Ballistic military jacker, velvet for-get-me-not, artist tintype, millinery ribbon.

20H” x 20L” x 7.5W”

Earthbags, 2014

143 hand embroidered yellow sandbags, embroidery thread, sand.

14W” x 24H” each bag, installation dimensions variable

Now and Then (diptych). 2014.

Custom tintypes mounted on wallpaper, velvet ribbon, vintage plaster frames, square cut nails, paint.

15H” x 12L” x 1.5W” each

Exhibition July 10-September 14, 2014 at Artpace, San Antonio, Texas

In-Residence Dates: May 20,2014 – Jul 14,2014

In March 2013, the U.S. military allowed women to serve in combat roles. But it is a little known fact that over 150 years prior to that, women had already fought in the American Civil War, albeit dressed as men. It is estimated that 400-1,000 women enlisted in disguise and fought for both the Confederacy and the Union. Some were discovered and sent home, while others fought as men with distinction and came out as women when safely living again at home. For soldiers like Sarah Rosetta Wakeman (also know as Pvt. Edwin Lyons Wakeman) their gender was only discovered upon death on the battlefield or in an army hospital. A few such as Jennie Hodgers (Albert Cashier) continued to live as men long after the war only to be discovered because of illness, dementia, or death.

I wanted to show a connection between all of the women who chose freely to fight for their country despite all odds. Current headlines of rape and sexual harassment in the military show that discrimination based on gender and sexuality is both rampant and unresolved. I’m interested in the ways that these secrets echo both the actions of their predecessors during the Civil War and the more recent approach of “Don’t ask. Don’t tell.” While the latter policy is now dissolved through official policies more open to queer folks, a larger pattern in the military, related to the debates in society at large, reveals the difficulties that LGBTQ soldiers and their families still face.

Sargent Donna Johnson, whose initials can be found on one of the sandbags, was killed on October 1, 2012, in Afghanistan. She and her wife Tracey Dice are the first same-sex military couple to have suffered a casualty since the repeal of “Don’t ask. Don’t tell.” But because of the unresolved national debate surrounding same sex marriage, Dice wasn’t able to receive benefits until May 2014. Episodes like this frustrate many queer activists opposed to the fight for gays in the military who ask: What kind of progress is defined by a system that allows queer people to go into the military to die while having to fight for basic human rights in the very society that they are defending?

I wonder how our current military can evolve to include forms of gender and sexuality in an institution historically predicated on stereotypical ideas of masculinity such as bravery, strength, and aggression. How can they show compassion and empathy for “others” in the world if they don’t show those same sentiments in their own ranks? This is not to condemn the military or individual soldiers, but to point out the greater issues of gender and sexuality that are ignored and/or supported from the top down.

This exhibition uses a number of signs that point to the histories outlined above. The sandbags are embroidered with the initials of each woman soldier who has died for the United States since 2001. The famous 1863 photograph that serves as the basis for a pattern for the climbing wall and dress is A Harvest of Death by Timothy O’Sullivan, an image from the aftermath of the Battle of Gettysburg. A crinoline cage that was meant to bolster the volume of a woman’s dress becomes the basic architecture of a Civil War era tent. The sound piece is a collage of letters written by a female soldier during the American Civil War interwoven with ukulele renditions of the songs Soldier Boy and Bang Bang. Together these works construct a space of mourning as a way to move forward.

*Artwork originally commissioned and produced by Artpace San Antonio

Installation photo credit (except 3 tintypes) by Mark Menjivar